The son of artists Edgar Levy and Lucille Corcos, David Levy grew up in the midst of the creative community that moved the world’s art capital from Europe to New York during the seminal years of the late 1940s and early ‘50s. An internationally known and highly respected arts professional, he is an artist with an extensive and unusual background on the American art scene.

Heading New York’s Parsons School of Design for 20 years, Levy transformed it from a tiny and obscure academy to one of the world’s largest and most prestigious arts institutions. This was followed by his appointment as Chancellor of The New School, Parsons’ parent university, then by 14 years as the Director and President of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC’s oldest museum and largest privately supported cultural institution and most recently by ten years as President of Sotheby’s Institute of Art.

In his formative years, Levy’s family’s circle was a snapshot of artistic and intellectual life in and around New York. With their household/studio as its informal center, frequent visitors included his godparents, the sculptors David Smith and his wife Dorothy Dehner, modernist painter Jan Matulka (who was the elder Levy’s and Smith’s mutual teacher), the artists Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, Arshile Gorky, I Rice Pereira, Louise Nevelson, George McNeil, Vaclav Vytlacil, John Graham, Richard Lindner, Richard Pousette-Dart and many others, including art historian/critic Meyer Shapiro, philosophers Irwin Edman and Charles Frankel, and composers Kurt Weil and John Cage.

During the 1930s, Edgar Levy and the sculptor David Smith, his closest friend, shared a studio/workshop at Brooklyn’s Terminal Iron Works. By the early 1940s, both the Smiths and Levys had left New York – with Smith and Dehner moving to Bolton Landing in the Adirondacks and the Corcos–Levys 50-miles north of the city, to Rockland County’s fabled artist community on South Mountain Road. But their deep friendship required frequent and extended visits, so the Levy/Smith “family” remained intact.

Throughout this period, the younger David – Smith’s namesake – spent many months “assisting” both his father and his “Uncle Smith” from a perch on their respective studio floors. Under their discerning eyes he made objects from scraps of metal and other studio detritus and was introduced by them to the magic of photography, developing film and prints in trays precariously set on the Rockland house’s darkened cellar steps.

These hours of play and observation shaped Levy’s early visual sensibilities, as did the continued attention of his artist parents throughout his teens. Along with the Smiths, they nurtured his talents, helping him refine both his skills and creative voice; providing a strong foundation for a maturing critical judgment and technical ability.

Later, as a student, Levy studied aesthetics and art history, receiving a BA from Columbia College, Columbia University. He then enrolled for graduate work in art history at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, subsequently earning a PhD from NYU’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development.

Joining the staff and faculty of Parsons School of Design in his early 20s, Levy moonlighted as a free-lance photographer. He also assisted his photographic friends on commercial assignments ranging from fashion shoots to still life and portraiture. Later he became fascinated by the forms and settings of the industrial landscape, and a one-man exhibition of his work on this subject was held at the State Museum in Dortmund, Germany. In America his photographs have been exhibited at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, The Corcoran and the Storm King Art Center, among others, and reproduced in publications including The New York Times and The Washington Post.

An important influence was Levy’s long collaboration with the brilliant graphic artist and Art Director’s Hall of Fame laureate, Cipe Pineles, with whom he designed hundreds of books and other publications. Together they won numerous awards in recognition of their design excellence and creative innovation. Levy credits this experience and Pineles’ guidance with the refinement of his eye for balance, color and composition and for a fastidiousness about these relationships in both two- and three-dimensional work that his colleagues find remarkable (if annoying) but which his wife argues is a minor manifestation of Asperger Syndrome.

With a life-long interest in both the aesthetic and the craft of art-making, Levy has maintained a workshop-studio from his teens to the present, producing a steady stream of work – some of it practical or utilitarian, including furniture and cabinetry, as well as objects of a more artistic nature such as small sculptures, musical instruments (including half a dozen harpsichords of varying types and sizes) and many frames and moldings for his large collection of paintings and works on paper.

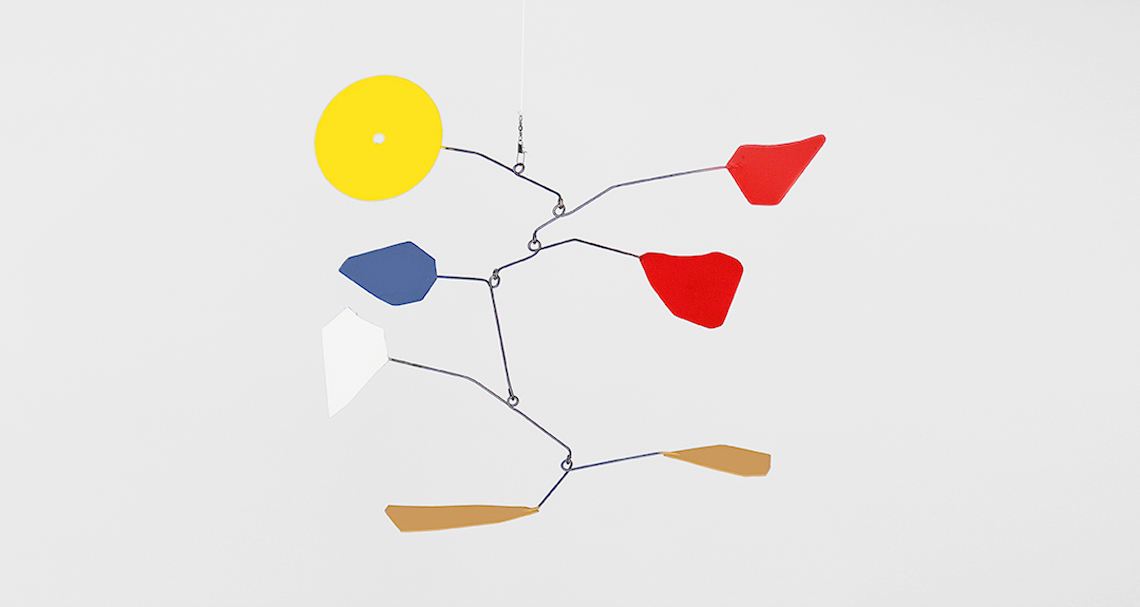

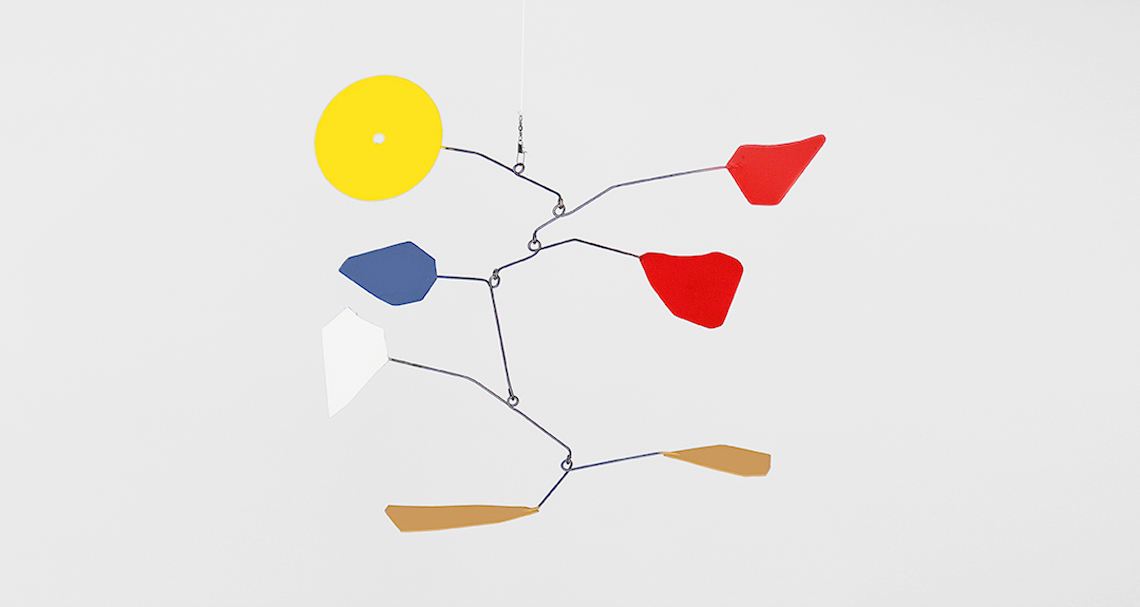

Levy’s interest in mobile sculptures began in his late teens during frequent visits to the home of his family’s close friend, the musician and recording impresario Mitch Miller. The Miller’s art collection contained a number of mobiles, along with original Toulouse Lautrec posters and other compelling works. But this early enthusiasm lay dormant for many years until his tenure as President/Director of The Corcoran, where he mounted an exhibition that included a large work by Alexander Calder. He hung it dramatically in the museum’s grand atrium and was so moved by its impact on the space that he tried to negotiate a long-term loan of the piece. Though this effort was unsuccessful, the imagery remained fixed in his mind and prompted him to experiment with kinetic forms of his own.

The result has been a body of work drawing on the modernist principles that shaped Calder’s art, as they did for so many American artists of their generation. An artist/art historian, Levy believes that all mature art, no matter how radical, builds on the foundations of the past and that while artists often share a common vocabulary, each brings a new personality, the nuances of a uniquely formed expressive direction and a personal vision that differentiates their work and moves it forward.

Just as many artists, including Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, and Gris, explored the excitement of analytic cubism through techniques so similar that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish one from another, Calder’s debt to the forms, palettes and compositions of Juan Miro, Fernand Leger, Arshile Gorky and others is clearly apparent. Yet by reinterpreting their images in kinetic three-dimensionality he placed them on an original new course. It is precisely in this spirit that Levy brings his own subtly different sense of color, spatial relationships and movement to the mobile sculpture tradition that Calder so brilliantly articulated.

“This is a wonderful and joyful art form.” says Levy. “It is important to build on its foundations so that it can evolve and be accessible to a wide public through the work and creative imaginations of many artists. And while we must acknowledge a great debt to the work of Alexander Calder, the development of this genre should not be inhibited by a critical community or a market that wishes to create a brand by artificially limiting its authenticity to the work of one individual.”

From the beginnings of recorded history art has been a necessity of mankind, expressing through its unique aesthetic our greatest hopes and deepest beliefs. As Thomas Merton has said, “Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.”

Our relationship to art is symbiotic. If art is to exist we must create it, and in its turn art returns the favor; repaying us with a metaphysical lens through which, as Merton suggests, we reveal ourselves to ourselves. Though often beautiful, it is simplistic to believe that the mere creation of beauty is either a necessary or sufficient condition for art. After all, our world is filled with endless other forms of visual splendor.

Creating art, then, is a conscious reinterpretation of objects and ideas through a purposeful act of communication in which elements and relationships are abstractly manipulated to change and/or emphasize their deepest meanings. At its best, art making is a process in which the artist draws upon both objective knowledge and subliminal impulse.1 But to be successful, art must also evoke a parallel response from its audience, transmitting simple information while plumbing hidden levels of consciousness, ambiguity and understanding.

For these reasons and more, our need for art is fundamental. It is a necessity of living; as important to our spiritual well-being as air conditioning in the summer and heat in winter are to physical comfort. It thus follows that a primary responsibility of the artist is to make work that is accessible; meaning within reach. But accessible is not a simple word. It can mean affordable or, in another usage, understandable; two very different inflections. Art should be both, for it is a defining artifact of humanity that all of us must possess – literally, psychologically and as part of our daily lives.

I make mobiles because they fulfill these needs and because there are few visual vocabularies that speak more directly or to more of us than the magical balance of three-dimensional shape, color and motion that is their very definition. Mobiles do not seek to bring catharsis, as in works like Picasso’s Guernica or Grunewald’s Crucifixion. Instead, mobiles lift our spirits, delight our eyes and, not incidentally, transform both our homes and our public spaces into a joyful world of color, movement and visual imagination. They are the other side of catharsis, evoking equally important and necessary emotion – pleasure, playfulness, happiness and a sense of well-being.

So I make art that is accessible in the full meaning of the word. It is both understandable and affordable – art that everyone can live with and which, through the hypnotic movement of its abstract shapes and colors, can be simultaneously lighthearted, beautiful and subliminally evocative. Completely of today’s time and place, these kinetic works recognize a debt to history and are steeped in respect for the traditions, talents and creative imaginations of generations of artists who have also explored the dual aesthetic that takes both artists and their art through and beyond the pleasure principle.

1. “If a man hacking in fury at a block of wood … make there an image of a cow, is that image a work of art? If not, why not?” (James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Chapter 5)